A type of immune therapy called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of multiple types of blood cancers but has shown limited efficacy against glioblastoma—the deadliest type of primary brain cancer—and other solid tumors.

New research led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, suggests that drugs that correct abnormalities in a solid tumor’s blood vessels can improve the delivery and function of CAR-T cell therapy.

With CAR-T cell therapy, immune cells are taken from a patient’s blood and are modified in the lab by adding a gene for a receptor that instructs the cells to attach to a specific protein on cancer cells’ membrane.

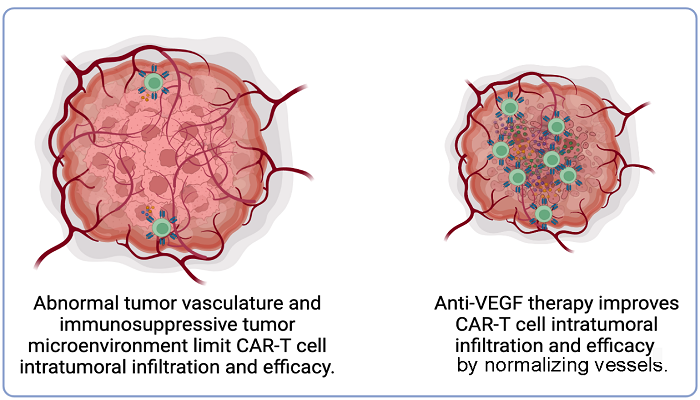

“One of the main reasons that CAR-T therapy hasn’t worked well against solid tumors is that intravenously administered cells are only capable of migrating to either the invasive edges of a tumor or only in limited areas of the tumor,” says senior author says senior author Rakesh K. Jain, PhD, director of the E.L. Steele Laboratories for Tumor Biology at MGH and the Andrew Werk Cook Professor of Radiation Oncology at Harvard Medical School.

“Also, tumors create an environment around them that is immunosuppressive, that protects them from CAR-T therapy and other anti-cancer treatments administered intravenously through the blood supply.”

Jain and his colleagues previously showed that “normalizing” tumor’s blood vessels with agents called anti-angiogenesis drugs, originally developed to inhibit the growth of new blood vessels, can improve the delivery and anti-cancer function of immune cells naturally produced by the body.

“Therefore, we sought to investigate if we could improve CAR-T cell infiltration and overcome resistance mechanisms posed by the abnormal tumor microenvironment by normalizing glioblastoma blood vessels using an antibody that blocks an important angiogenic molecule called vascular endothelial growth factor, or VEGF,” Jain explains.

Using state-of- the-art live imaging to track the movement of CAR-T cells into tumors in real time, the team found that treatment with an antibody against VEGF improved the infiltration of CAR-T cells into glioblastoma tumors in mice. The treatment also inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in mice with glioblastoma.

“Given that an anti-VEGF antibody—bevacizumab—has been approved for glioblastoma patients and that there are several CAR-T therapies being tested in patients, our results provide a compelling rationale for testing the combination of vascular normalizing agents, such as anti-VEGF antibody, with current CAR-T therapies,” says Jain.

“In addition, our approach may also improve CAR-T therapy against other solid tumors. Therefore, we plan to extend our research to other tumors.”

Additional study authors include Xinyue Dong, Jun Ren, Zohreh Amoozgar, Somin Lee, Meenal Datta, Sylvie Roberge, Mark Duquette, and Dai Fukumura.

This work was supported by the National Foundation for Cancer Research, the Ludwig Center at Harvard Medical School, the Jane’s Trust Foundation, the Nile Albright Research Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.

About the Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The Mass General Research Institute conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the nation, with annual research operations of more than $1 billion and comprises more than 9,500 researchers working across more than 30 institutes, centers and departments. In July 2022, Mass General was named #8 in the U.S. News & World Report list of “America’s Best Hospitals.” MGH is a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system.

Source: Massachusetts General Hospital